The Making of a Cookbook

Starting the Book

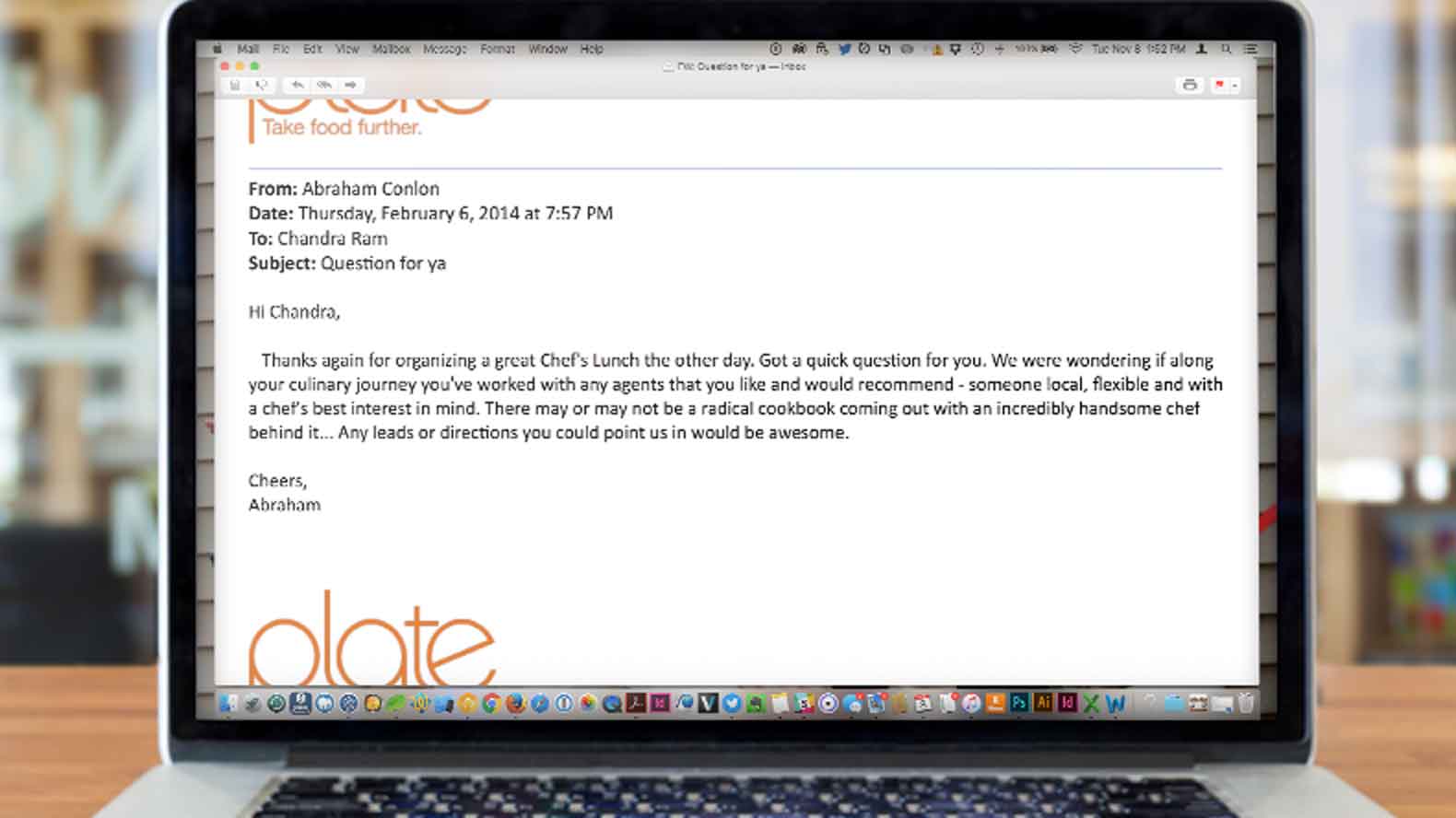

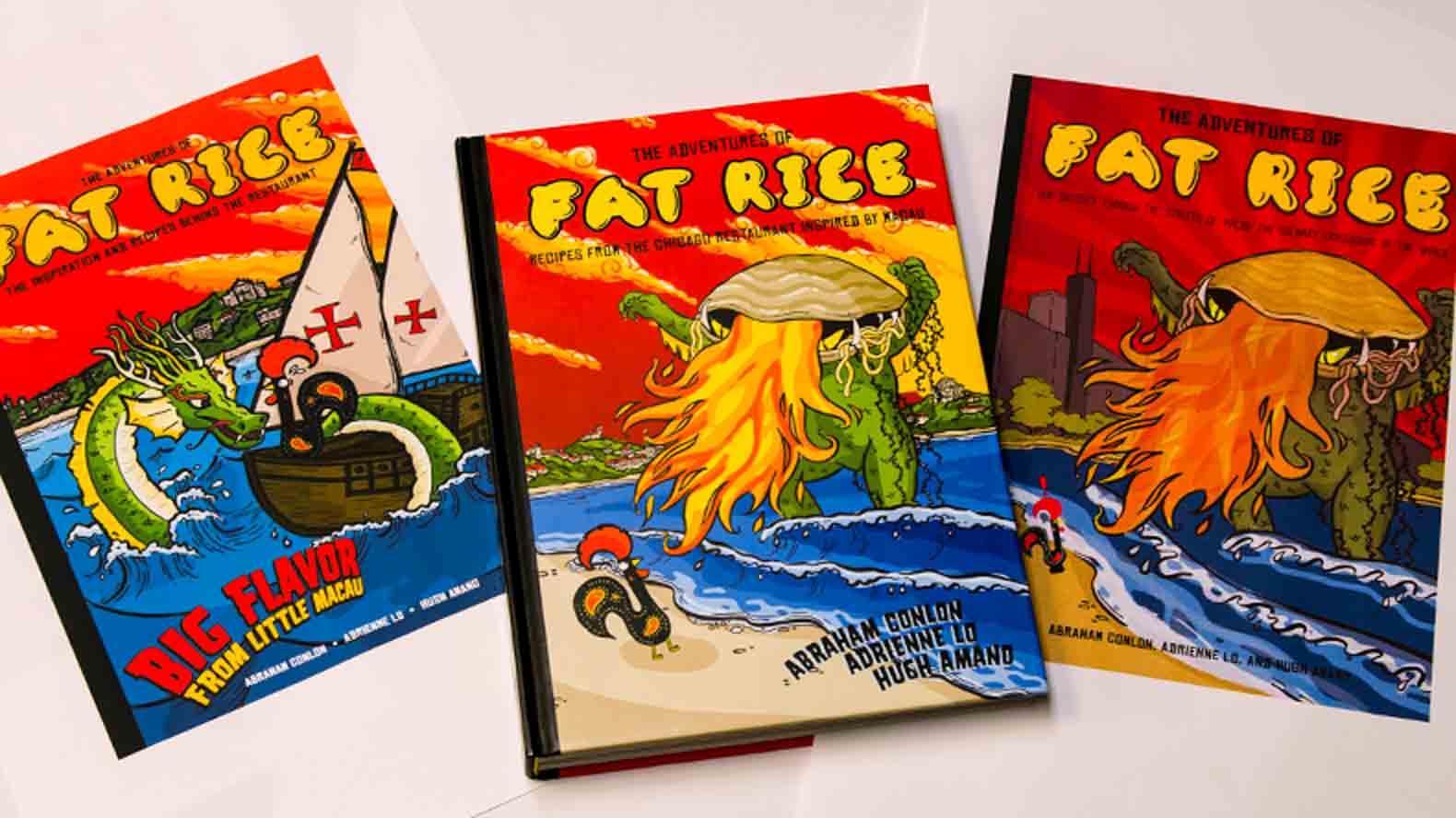

The apprehension they felt was justified. There is a lot more to putting a book together than just selling a publisher on the idea. They had to figure out how long the book would be, the schedule for when they would turn in various drafts of the book, what the resulting book would cost ($35 is the norm for hardcover restaurant cookbooks, Timberlake says) and a million other details, not the least of which was the book’s design.

“The publisher decides who will design the book, but it’s almost always an in-house designer,” Collins says. “They will never, ever, let go of control over design. It’s a short discussion, but important for authors to hear; they often want to have a friend to design it.”

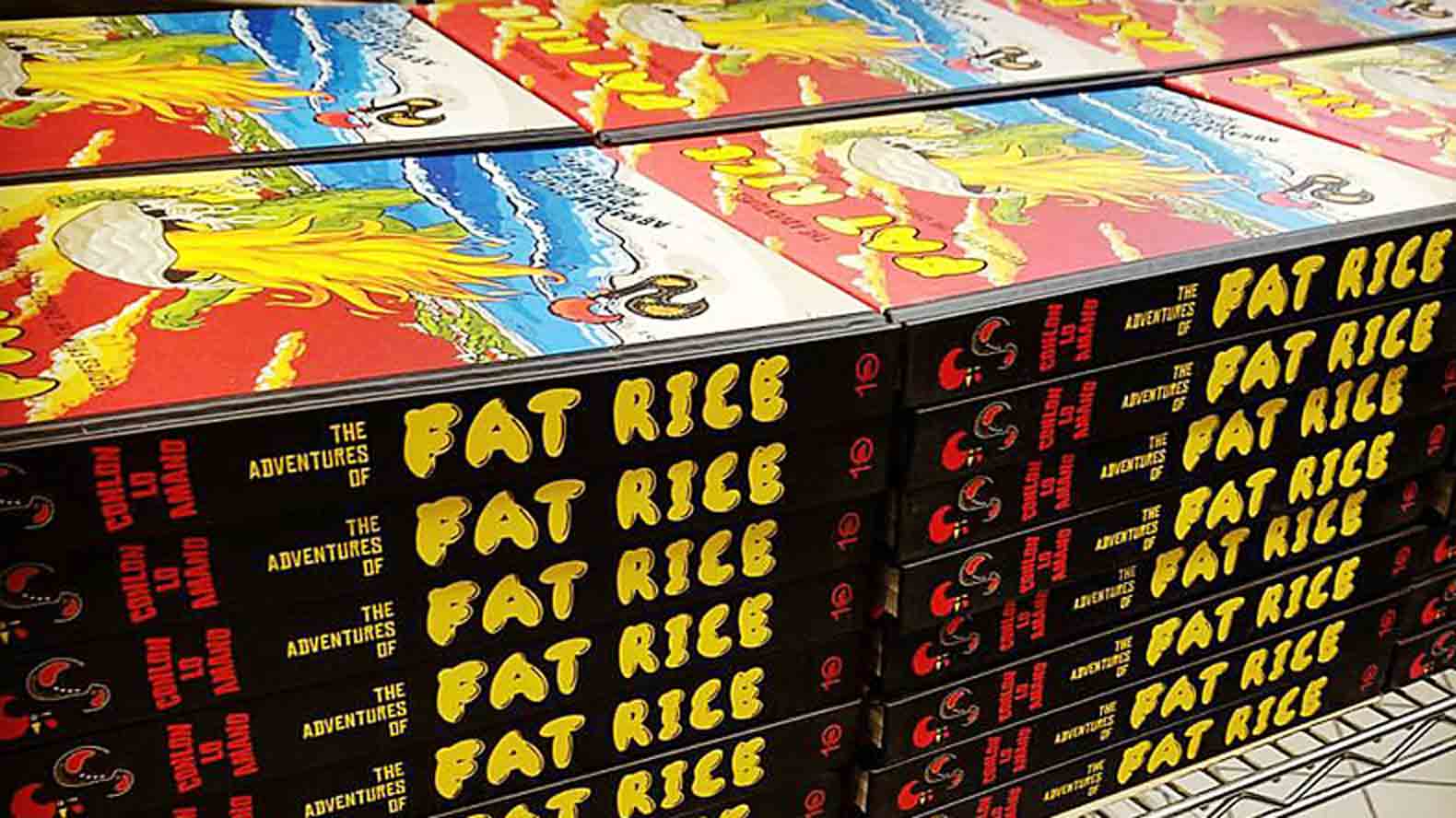

Design was especially important to the Fat Rice team, who had included a huge amount of illustration in addition to photography in their proposal. They had definite ideas about what their book should look like.

“First, we got on a call with the team, and knocked out a vision for the book,” Plikaitis says. “We looked at the proposal, and mapped out everything. It takes time; you have to discuss colors, fonts, everything.”

"We refined it with them until they were happy with it," Timberlake adds. "Sometimes the authors don’t have a lot of ideas, but in this case, they had a lot of say.”

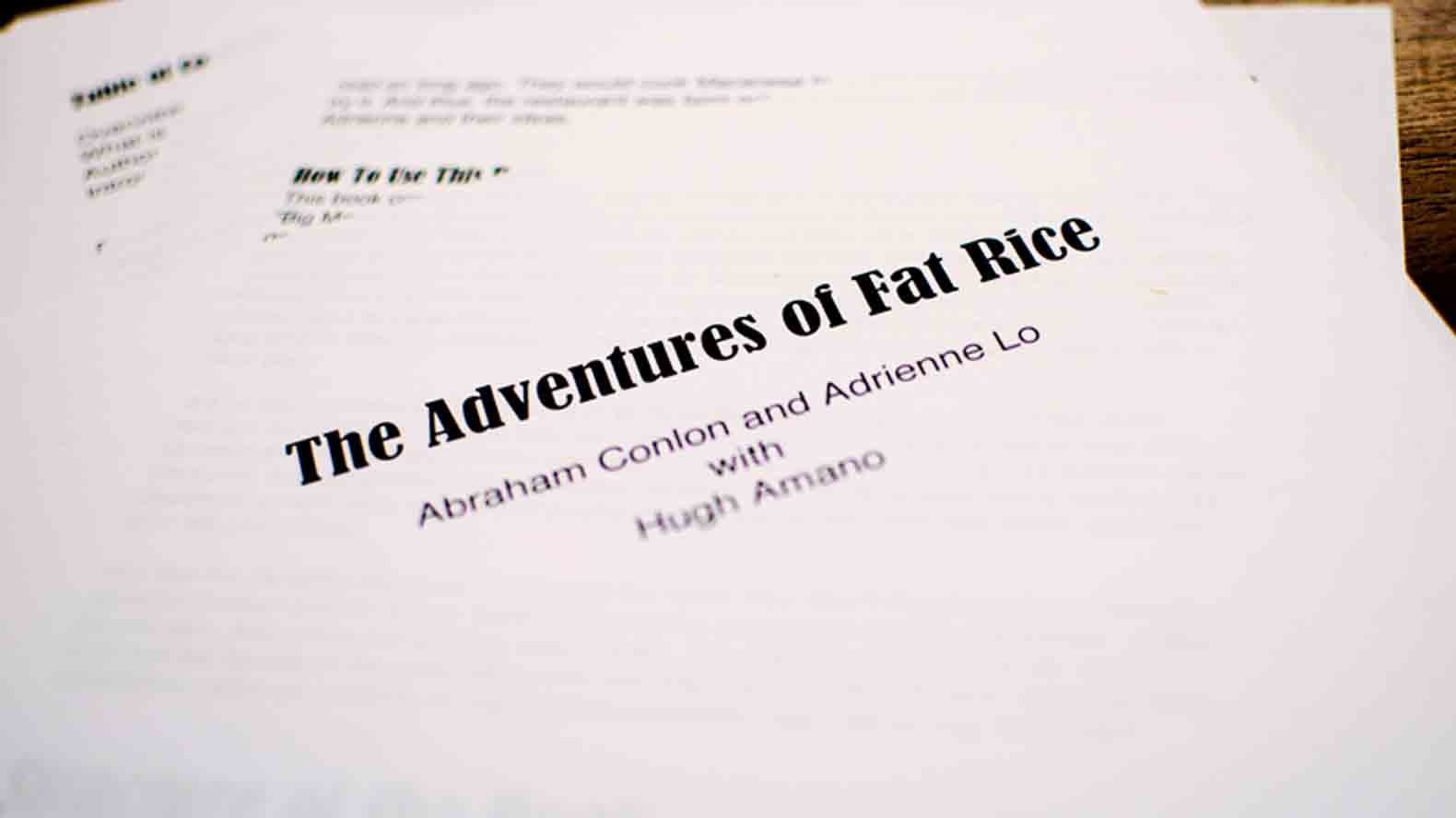

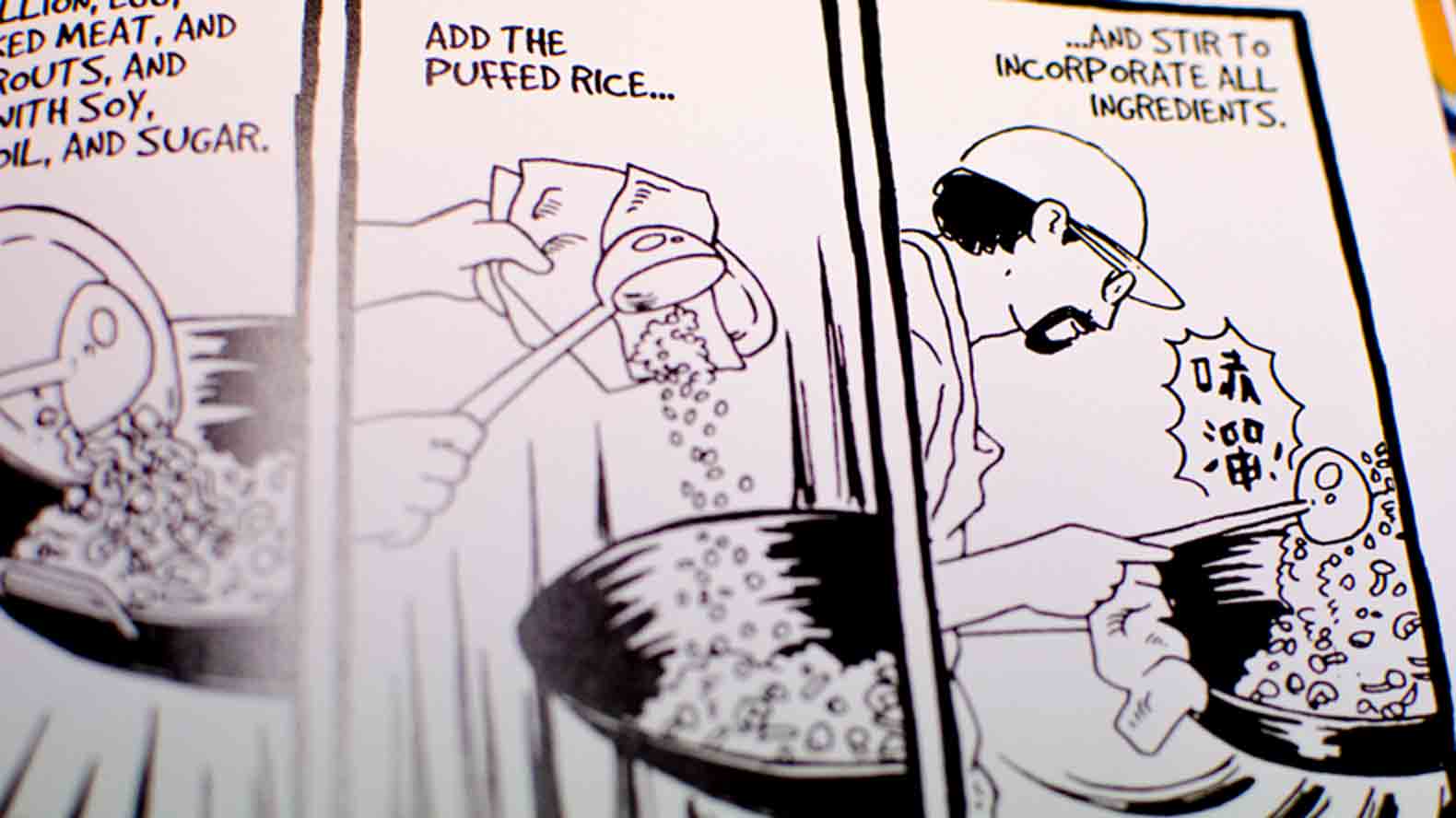

“My first thing was that I did not want it to look like a cookbook,” Conlon says. “I wanted someone to be in the cookbook section, being like, ‘Why is this weird graphic novel here?’”

“Abe really wanted the book to be chock-full of visual info, have lots of text and overlaying photographs," Timberlake says. "If a recipe ran long, he wanted us to overlay it over an image. He wanted us to put in as much art as we could.”

Part of the planning included setting a budget for what photography Ten Speed would cover, which included the photography from the trip to Macau the team had included in the proposal.

“We knew Macau was integral, so we built it into the photo budget,” Plikaitis says. "We needed to see this amazing place with the people and cuisine, but also needed to do a studio shoot.”

Conlon and Lo had pitched the book with a photographer in mind, but the project hit its first speed bump when the group from Ten Speed wasn’t happy with that choice.

“We definitely had some concerns about test images,” Plikaitis says. “There are certain acquisitions that come with a particular photographer, but others where you hope they will be open to your suggestions and work through it. It’s definitely a very tricky conversation to have, but we all have the best intentions for them and their book.”

Ten Speed asked the Fat Rice team to consider other photographers for the book. Dan Goldberg had photographed Cookie Love, Mindy Segal’s cookbook that was agented by Collins and was published by Ten Speed. He had also just sold a food/photography book about Cuba to Ten Speed. Plikaitis asked Conlon and Lo to meet him and see if he might be a good fit.

“Ten Speed showed Abe and Adrienne the work that we had done for Cuba!, and they loved it,” Goldberg says. “It had the grit and feel they wanted for the Fat Rice book. I ended up meeting them at the book launch party for Cookie Love. We had a chance to talk, they called a couple of days later, came over to my studio and we drank some wine and ate some charcuterie and talked.”

Goldberg signed onto the project, with a plan to join them for a couple of days during the Macau trip, and do studio shots as well.

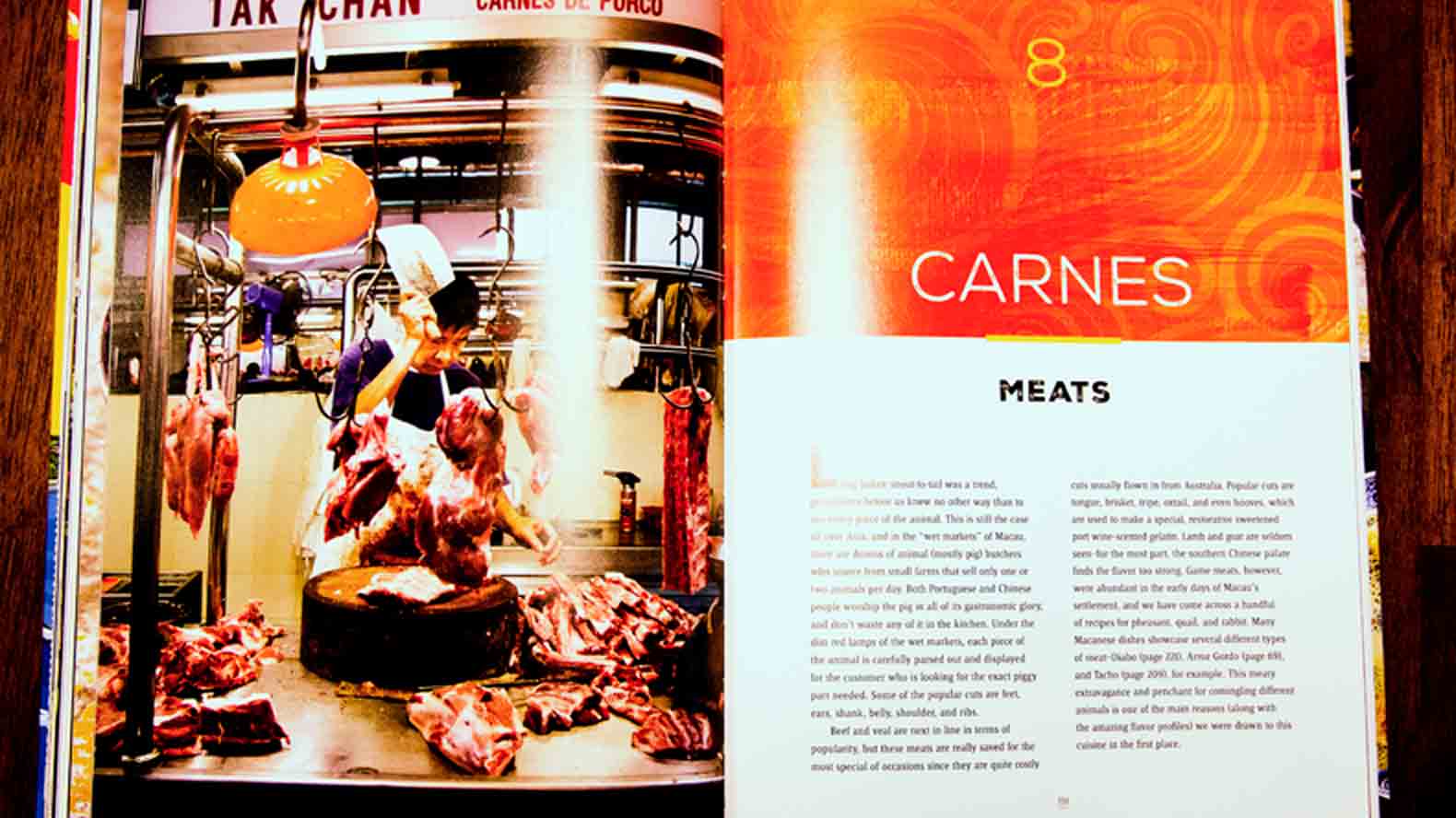

“We chose Dan because he had an aesthetic that he could make things that were relatively gruesome look beautiful,” Conlon says. “I understand as a chef that food is not always this beautiful hero plate. It’s the chicken getting the blood out in the butcher. It’s a guy chopping meat with a cleaver. A fish with its head on, still breathing, ready to be killed. Rabbit with fur still attached. Blood and guts. You go to these markets and learn that food is real and food is life and food is dirty. This is real life; this isn’t glamorized chef life. Dan had a look and aesthetic that resonated with us and offered a cool contrast to the fun, playful imagery we had with the illustrations.”

The opening image for the meat chapter Photo: bert ganzon

Writing the Book

The difference between a chef who dreams about writing a book and a chef who’s written a book is how they each define the act of writing a book. The former thinks it’s the easy part, and the latter knows it is actually incredibly time-consuming. Writing a book is a lot more than cutting and pasting your recipes into a word document, writing a few pithy introductions and hitting send, as the Fat Rice team would soon learn.

“We had a lot of the recipes standardized for the restaurant, so we thought, ‘Oh, this isn’t going to be that hard,” Conlon says. “Which was… wrong.”

Amano had left the restaurant by this point, so was able to focus on writing the book and keeping all the information—from notes about Macau’s history to the proper technique for frying salt cod.

“Abe is brilliant because he thinks so big,” he says. “It was my job to add structure, to make it earthbound. He has to be pulled out of the despair of being a restaurant owner, which is about dishwashers breaking down. I can’t imagine us doing this book if I was still working directly with him; it would be too easy to get distracted by things. Me being removed from the restaurant really helped with the process.”

“We had a lot of the recipes standardized for the restaurant, so we thought, 'Oh, this isn’t going to be that hard.' Which was… wrong.”

Abe Conlon, Fat Rice

The team met weekly to work on the book, bit by bit. Amano would take notes on their conversations, then write more in between meetings.

“I would structure things for each week’s meeting, send them an email with bullet points of what we had to go over, and we’d get together at the restaurant, my house or their house. The meetings would go from 5pm to around 1am, more or less. I sent them notes in advance, and sometimes Abe would prepare something, but I would go away and make it legible and pretty. I’d get the raw content, shape it up, and review it. Essentially, my role in addition to writing was managing the project, so it was my job to keep everyone in line and on time.”

Amano regularly sent copy back to Timberlake for review, so that there were no surprises with the manuscript.

“Well before the manuscript was due, they sent in some narrative text and recipes, and we had a few calls about big picture and structural questions,” she says. “How the recipes should be presented; do we give units by weight, volume or both? We came up with rules we would apply to the entire book; it was good to do that early on.”

Back to Macau

Of course, the book is more than just recipes; it’s about the history and culture of Macau. The fact that their cookbook would be most readers’ first experience with Macau wore heavily on the team; being true to the place and its people was incredibly important to them. Conlon, Lo and Amano started working on writing and recipe development in the spring of 2015, but they needed to go to Macau for research, especially since Amano and Goldberg had never been. They worked with Timberlake and Plikaitis to map out a plan of what they wanted to photograph: iconic sites, street scenes, the food, and the people. In October 2015, they headed to Macau, and planned to also visit Malacca, Malaysia and Singapore. For the newcomers, it was a trial-by-fire.

“It was so cool to go with Abe after he’s formed all these relationships; it meant we had friends already,” Amano says. “The first night we were there, Marina [Senna-Fernandes, a Macanese food expert] had us over to her house for dinner, for her husband’s 50th birthday dinner. It was awesome, but it was a little uncomfortable at first; there were only a dozen people there, all Chinese, Macanese and Portuguese, and us, right off the plane. Her husband was Swedish, so he pulled out a bottle of aquavit and we stayed up all night, drinking with them.”

“I remember at midnight, going over to Hugh, and saying, ‘Hey, I think we should all get back to the hotel; we have to get up early,’ and he was like, ‘Man, if you’re going to hang with us for three weeks, you’d better figure this out,’” Goldberg recalls. “So we stayed up all night and then shot the ruins at 5am, and then had breakfast and went to bed. And that’s kind of how the whole trip went. I had a one-year-old daughter at home at the time, so was used to not sleeping much, but this was something else. I knew I had to figure it out quickly if I was going to survive.”

“Traveling with Abe and Adrienne is a whole other story,” Amano says. “It’s challenging, but really rewarding. We tried to talk with the people there a lot, since so much of this food doesn’t really exist in restaurants anymore; it’s in the homes. Abe’s the kind of guy, where if you’re standing outside a shop, and not sure if you want to go in, he goes in, and just starts talking to the guy and starts pointing at things and asking questions. It can be a little uncomfortable at times, but it’s gold.”

Conlon and Lo had timed the trip to coincide with the 100th birthday celebration of Dona Aida de Jesus, who had become a mentor to them.

“It was amazing. Dona Aida de Jesus invited us to her birthday party,” Amano says. “That’s super-special, to have spent the previous two years writing about the food and the place and people, and then to be standing there, shaking hands with a lot of these characters of Macanese cooking at this party. It was amazing. Not to get too sappy, but to me, that’s what it’s all about, that connection.”

When they weren’t meeting with friends and contacts, they spent their days walking around Macau, finding interesting images to shoot, but not knowing how they would fit in the book.

“Dan captured the spirit of what we wanted to convey,” Conlon says. “It’s somewhere between this fantasy world and this world of reality that doesn’t seem real. You look at this picture of a guy at the beginning of the meat chapter, this guy has a huge cleaver, chopping meat, and his sign is written in Portuguese and Chinese. This is it; this dichotomy. Those little visual snippets are what we find so interesting about Macau; bringing multiple things together to create harmony. That was the general idea of the aesthetic of the book—let’s take all these things that have made up the restaurant."Next

More about the Making of a Cookbook

- Log in or register to post comments